|

The artist is fundamentally alone in the creative process, whether he/she is

supported and encouraged by other artists and lovers of art, or is solitary.

The inner drama, the complex ebb and flow of feelings, hints and glimpses

of images and ideas, the inner drive, urges, promptings and doubts --

the often fierce, undeniable, gut-deep need to create -- are those of

individual artists alone, that they must somehow deal with through visions

of the beauty and torment of the world.

Artists are meant to probe heaven and hell, good and evil, beauty

and ugliness -- the full dimension of life on earth, humanity's relations

with itself, with nature, with God, and the universe, as their personal

needs and interests dictate.

The creative urge may be difficult to define, but all artists know

it, have experienced it to greater or lesser degree. Its insistence

will not let you be. You have to act on it, as you would any other profound

physical or emotional need.

Whether tired or ill, discouraged or otherwise wounded, the artist

goes to his easel to assuage the force within demanding that he act,

demanding its release, demanding its expression.

Because this creativity is so much a part of the artist, to deny it

would be like denying a lung or kidney permission to function. No wonder

artists have spoken of their "muse" or, more forcefully, their "demon."

The demands that the fundamental creative drive makes on human beings

are not light and casual ones. It is a force to be reckoned with (this

is not to say that artists can never rest, that they should feel guilty

if they do. But at times they are pushed through fatigue and difficulty

by the intensity of the creative force).

|

|

The old joke -- a somewhat sick one -- "when the creative urge hits you, lie

down until it goes away," is not good advice. The avoidance or trivialization

of something so profound can only lead to unhappiness and regret.

The greatest fear that artists can have, or should have -- if fear

of any kind is called for -- is not of failure or success, but at the

end of their lives looking back and seeing that they never really tried.

They never really took art seriously enough.

They never pushed the limits of their stamina, feelings and perceptions,

never took some chances on the canvas.

One of the truly peculiar things about creativity is its ebb and flow.

Sometimes inspiration, motivation are strong and undeniable, other times

so weak that to work takes an act of will and courage to reach the level

of mere plodding. Yet, significant art can result from both conditions.

When artists feel in total command of their means, the process flows

smoothly, fluently, irresistibly, vibrantly to its conclusion. Thought

or rational mind play little or no role. The artist and the creative

process seem as inevitable as forces of nature (which they are), a high

wind, the sun's intensity, a torrential downpour, the insistence of

leaves and buds in spring pushing their way through warming earth and

bark to reach the light.

Other times, the artist is a stranger in a strange land. What is this

thing? A paintbrush? What am I to do with it? The once-natural, nearly

unconscious procedure of raising brush from palette to canvas and back

again has been interrupted as if nerve fiber had been cut.

Like a .350 hitter who suddenly, inexplicably, can't get the ball

out of the infield, the artist experiences a slump, a loss of naturalness.

The flow of cause and effect, stimulus and creative result is broken.

|

|

The only thing the artist can do, the only thing the hitter can do, is keep

painting, keep swinging at the ball. Sooner or later, contact will again

be made, the creative rhythm will reassert itself.

One suspects that Cezanne was such an artist. He was never conventionally

technically fluent despite his marvelous gifts of color and dense, intensely

substantial form. To look at a Cezanne painting is to sense the struggle

to "realize," as he put it, his vision, his inner feeling of the form

and meaning of things.

Artists feel incomplete without the intimate relationship with nature

and life that the creation of art implies. Unlike an animal, tree or

rock so naturally part of the world that it has no concept of alienation,

no troubling separateness from nature, the creative process helps the

artist overcome, at least temporarily, this painful human characteristic

and sink deeply into nature's matrix.

|

|

Some artists think, others don't think a whit. Both are equally valid. The

latter function automatically, instinctively, almost like compost. For

most artists, art is a blend of thought and feeling. But all artists,

to be significant, must work mainly from instinct, from the inner mysteries

of feeling and responsiveness.

After the creative act is well underway or ended, analysis is useful

in evaluating the work and solving problems (a mural obviously requires

more preliminary planning than an easel painting). But the contemporary

disease of over-rationality -- starting a painting from the head rather

than the heart -- will chill it, will likely kill it, leading to art

that gives off little light or heat for the warming of the soul.

Beyond the vagaries and uncertainties intrinsic to art at any time,

are the difficulties and confusions of an age such as ours when art

values, traditions and principles lie like rubble in the streets of

a shattered civilization. In such an environment, it's every artist

for themselves, trying to make what they hope is art, whether it is

or not.

|

|

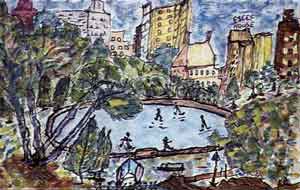

What, then, is creativity? Creativity is what happens when the raw material

of reality is filtered through a consciousness and transformed into

a significant artistic vision. Creativity is responding to the profundities

and miracles in nature and life that are commonly devalued, depontentized

-- simply not noticed -- by the curse of human blindness and the mediocrity

of the mind-numbing routine imposed on everyday existence.

Creativity is Cezanne seeing and sensing the poetry and mystery of

life in the form and color of an apple (that tens of millions of people

never see, they only eat), which he translates into timeless, organic,

densely-molded art.

Creativity is Hieronymous Bosch manifesting the struggles, forces

and counter-forces within society and the psyche through brilliantly

imaginative, disturbingly bizarre symbols and images of humanity. It

is Rembrandt's unparalleled probing of the soul by means of an equally

unparalleled grasp of rich paint-paste creating the corporeality of

human flesh, the very material of physical reality.

|

|

Creativity is Henri Toulouse-Lautrec's ability to see the artistic possibilities

in subjects from the underbelly of life, in "At the Moulin Rouge," adding

a strip of canvas to this great, nearly finished painting to make room

for a large, wonderful, light-filled, "dream girl" with red lips, turquoise

forehead, yellow hair and black hat. She pauses for a moment in the

foreground of the picture, a glorious antidote to the glum group of

intellectuals and prostitutes at the center table and the artist himself

walking through the club, dwarfed by his infirmity, bad luck and tall

cousin who accompanies him.

Creativity is the poet's turning the common usage of words into the

brilliant beauty of language in the service of revealing life to mankind

in this final stanza from "Dover Beach" by Matthew Arnold:

Ah, Love, let us be true

To one another! For the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

|