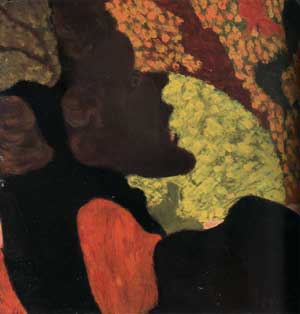

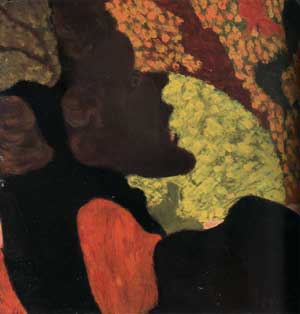

At the Divan Japonais, c. 1890-91.

Oil on panel, 10.6" x 10.6".

Private Collection.

At the Divan Japonais, c. 1890-91. Oil on panel, 10.6" x 10.6". Private Collection. |

In 1890-91, Édouard Vuillard created a remarkably concentrated image of the performer Yvette Guilbert singing, At the Divan Japonais, in oil on a very small panel of little more than ten by ten inches. The cabaret subject was not that unusual for artists and intellectuals of the time. Nor was the degree of caricature describing Guilbert's schooner face, seen in profile from the back. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was practiced at both, though he apparently didn't approach the popular singer until four years after the younger Vuillard had painted her. But there are significant ways in which the painting is radical, ahead of its time, even in the context of Vuillard's close-knit group of contemporaries. Like his good friend Pierre Bonnard, Vuillard simplified and abstracted shapes, but with far greater dramatic character and contour, and to the point of intense allusiveness and elusiveness. |

| Like Paul Sérusier, he produced brilliant, shimmering patches of color, but in stark contrast to dark areas and explosively contained in definitive shapes. The powerful, dark figure of Guilbert seems to be breathing out the yellow circle of her fan and the mysterious orange field beyond it in the audience. Like Gauguin in Jacob Wrestling the Angel of 1888, he devised an absolutely interlocking composition of shapes and sinuous line experienced over the shoulder of the protagonist. And like no one else at the time, he managed to suggest deep space while completely compressing it into a flat pattern on the surface of the picture. Vuillard was uniquely adventuresome in his early work, and he remained so throughout his career. More importantly, his pictorial explorations and innovations were connected with people, places, and scenes to whom and to which he had deep attachments. |

Large Interior with Six Figures, 1897. Oil on canvas, 35.5" x 76.6". Zurich, Kunsthaus. |

|

At the age of twenty-one, his last year at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1889, Vuillard was already part of the avant-garde. He joined the circle of the Nabis (who named themselves for the Hebrew word meaning "prophet"), along with Bonnard, Sérusier, Paul Ranson, Maurice Denis, Kerr-Xavier Roussel, and others who espoused the ideas of Gauguin concerning abstraction, symbolism, and primal motivation. He was a central figure in the progressive theater of the 1890s, producing scenery, posters, and programs for productions of plays by Maurice Maeterlinck, Henrik Ibsen, and others, usually under the aegis of his good friend Aurélien Lugné-Pöe. He was a major contributor to La Revue blanche, the most important journal for French, as well as other European, writers and artists throughout the 1890s. Vuillard certainly paid attention, more than most, to the changing abstract ideals of painting during this period--to the independent expressiveness of color, shape, and line; to the importance of decorative structure; to formal symbolism and double meanings; and to the teachings of the past. He was as well read and better acquainted with the work of his predecessors than any of his contemporaries. But he was also unique in turning his attention to the human drama, literally in the avant-garde theater and even more tellingly in works involving his family and friends and the intricacies of his responses and relationships to the world around him. Whereas Sérusier, Ranson, Denis, Roussel, and often Bonnard mythologized (and sometimes Christianized) their worlds, Vuillard realized his. As one who could write--"There is a species of emotion particular to painting. There is an effect that results from a certain arrangement of colors, of lights, of shadows. It is this that one calls the music of painting. . ."-- he wasn't necessarily a realist. It is just that his was an odd, more advanced sensibility in the age of Symbolism, less distorted and encumbered by ideology and generalization. |

Ile-de-France Landscape: Window Overlooking the Woods, 1899. Oil on canvas, 98.1" x 149". Art Institute of Chicago. |

| In every work we find ourselves inside Vuillard's life with his mother Marie, his sister Marie, his brother-in-law (Roussel), his lovers Misia Natanson and later Lucy Hessel, their husbands Thadée Natanson and Jos Hessel, his dealers the Bernheims, grownups and children he saw in the park, etc. Everything and everyone is familiar to him and therefore to us, and it immediately matters how each person is placed, how patterns merge and relate to one another, how the light is distributed, what is going on. It is not possible to know exactly what is going on in any given scene, except rudimentarily, for instance, that Madame Vuillard's daughter and their young seamstresses are at work. Nor does it matter, in certain respects. But it is almost impossible not to be aware that, within a very small compass perhaps, a great deal is happening, and already has to bring us to this point. |

Interrogation of the Prisoner,1917. Distemper on paper mounted on canvas, 43.3" x 29.5". Paris, Musee d'Histoire Contemporaine. |

Great efforts have been made to determine the exact site and occasion of Large Interior with Six Figures, and it seems probable that it represents a gathering in the home of Paul Ranson and his family around the time of Kerr-Xavier Roussel's affair with Ranson's sister Germaine. In any event, the actual story, though ultimately essential, is less important to know than the enormously complex weaving of motifs it might involve. There are hundreds of things in play: the patterns of rugs, curtains, wallpaper, and papers on the table; the attitudes and gestures of the people in the room, standing, sitting, opening or closing a door, peering at a document, bent over looking for something; the subtle interplay of dark and light, both in color and in illumination; the complex mesh of verticals, horizontals, and diagonals. |

|

It seems as though nothing is left to chance in the structure of this painting, but it is a structure that leaves everything to chance. Each figure has its own space: Vuillard's mother on her chair and rug receding diagonally to the lighted window on the left; Germaine Ranson facing her and away from us, standing on another rug that is turned slightly toward us; Ranson seated (next to a young woman standing) at the table in the center, which shoots diagonally back to the left; Ranson's mother contained in deep space by the door and its trapezoidal apron at the right, next to a vertically striped curtain, like Vuillard's mother; and another young woman almost out of the picture frame on the right, bent over a chair and behind a vertical pulled-back curtain. Just as the variously patterned rugs and other elements are made to fit the structure almost in celebration of their differences, so do the figures confront one another from their separate spaces, uneasily, perhaps, but inevitably. And within this structure is an inner life, countless things in play within the hundreds of things in play. Vuillard was not a realist in the sense that he detailed every feature of a person's face or of a rug's design. In other paintings, he moved closer and further away from that mode, but he generally understood the realization of detail as the movement of his brush related to every other movement of his brush. The entire scene has relentless, overall life because every object or shape (every moment) and every stroke within it is saturated with light (or darkness), color, gesture, and texture. Vuillard has found a way to encompass an extraordinary range of contradictions, like nature does in its juxtaposition of the details of earth, vegetation, animal life, sea, and sky. |

|

It has been confounding to critical discourse that the "intimist" Vuillard, like several of his contemporaries, produced some rather large paintings, including this one (about three by seven-and-a-half feet) and even more so the extensive decorative schemes he did for patrons in and around Paris. But, of course, he was only a "decorative" rather than an intellectual painter who dealt with "domestic" (female) subjects rather than big ideas like the nature of light (Monet) or the nature of pictorial space (Matisse and Picasso). Further confounding is the fact that he ventured outdoors, mostly from 1894 on, to the parks of Paris and to countryside in Switzerland, Normandy, the Ile-de-France, and elsewhere, for such works as The Window Overlooking the Woods, one of two huge landscape paintings (about eight by fourteen feet) he did in 1899 for the library of Adam Natanson's apartment in Paris. AnneVaillant, Natanson's granddaughter, remembered as a child escaping "into the painted landscape which is more real than real, absolutely actual, and unlimited--with its poplars and its hillsides. The pointed steeple of the little church, and in the middle ground a little white house . . ." There is a reason to go into the landscape, to search for things, to look further and farther, not because it is so naturalistic but because everything in it has been paid attention to in relation to everything else: the shapes of the trees and buildings, the contours of the land, the tiny figures that are nonetheless so important to the vitality of the painting. The view is not an actual one but a composite of views that Vuillard observed and knew quite well. It has the mythologized character of landscapes by his fellow Nabis, and for Anne Vaillant it had the endless perfection of a fairy-tale world. The articulation of space and depth in horizontal bands; the closely valued meshing of blues, browns, greens, and yellows; the interweaving of abstract shapes; and the fictionalized feeling of the place itself all evoke medieval tapestries, with which Vuillard was admiringly familiar in the Musée Cluny in Paris and elsewhere. This is quite in keeping with the overwhelming tendency of the time, among the followers of Gauguin, the Nabis, the Symbolists, and others to seek out earlier or exotic, what were considered purer forms of expression. But, of course, the hunt for the Unicorn is the magic and drama always of what Vuillard knew, in the city, in the countryside, among his family and friends, and how complicated he knew it to be. He was interested in an open, active present, or presence, rather than the past or passive present of Bonnard, Denis, Roussel, and even Matisse. |

Self-portrait in the Dressing-room Mirror,1923-24. Oil on board, 31.9" x 26.4" New York, Dian Woodner and Andrea Woodner. |

It is not surprising then that he took photographs

through much of his career (more than 2,000 images have survived), beginning

in the mid-1890s when Kodak marketed an improved camera for non-professionals.

Occasionally he used them as aids in remembering poses and places for his paintings,

but more often, and typically, he was simply devoted to and interested in the

moments and people of his life. He took many of his mother, of course, just as

he included her in many of his paintings, and those that he shot of her just

before her death in 1928, frail and smiling in the eccentric geometry of their

Paris apartment, are among the most loving and courageous images of the 20th

century. |

|

With the turn of the 20th century, after a decade of intense activity in the midst of the avante-garde, Vuillard's art began to change, ironically to become less abstract and more decipherable in terms of perspective space during the years when Fauvism and Cubism were going in the opposite direction. His people become somewhat more substantial, more embodied, and the vistas more open. But an even greater change occurred during the first world war, when he served for a while, at the age of 46, as a railway patrolman, photographed and painted scenes in a munitions factory, and was then briefly an official war artist, sent to the front for a couple of weeks in 1917. The one work that came out of this latter experience is Interrogation of the Prisoner, which he executed back in Paris. All the lushness of shape, color, and movement in his earlier work has been stripped down to a barren room in which the gaunt German soldier is held by two French soldiers and questioned by a third, seen only partially from the back. There is an implied analogy that makes the artist himself the interrogator, and it is in that critical spirit that the remainder of Vuillard's work, until his death in 1940, at the beginning of the second world war, can be understood. Vuillard had always been keenly aware of everything around him. He was unusually voracious in that respect. But now he is locked into the person or persons in front of him, and the admission is that everything in the surrounding space is an extension of their consciousness rather than the artist's. This represents a certain kind of maturing, which involves critical distancing even as physical features and the person's life become clearer. In other words, it is not fair to take over the life of another person, and the German prisoner, with his bleak demeanor and vague features, was the beginning of that understanding. Madame Vuillard's singularity is apparent in her son's last photographs of her. What was once an extension of Vuillard's imagination, his world, now belongs elsewhere, to others, to be entered into. He is no longer in his own house, protected by familiar places and longstanding relationships. Empathy is not diminished, but it is associated increasingly with a more or less florid objectivity. |

| Much of what Vuillard did after the war is associated with the act of looking, with people looking at works of art, a cast of the Venus de Milo looking at his mother, portrait subjects looking at the artist, or slightly away from him. In Self-portrait in the Dressing-room Mirror of 1923-24, the aging artist, with his white beard, looks up perhaps to something outside the realm of the picture. The focus is completely on him in his room, and we ultimately notice that his image in the mirror is hemmed in by reproductions of works by Michelangelo, Le Sueur, Poussin, Hiroshige, and other artists who have defined his life, beyond which he seems to want to see. |

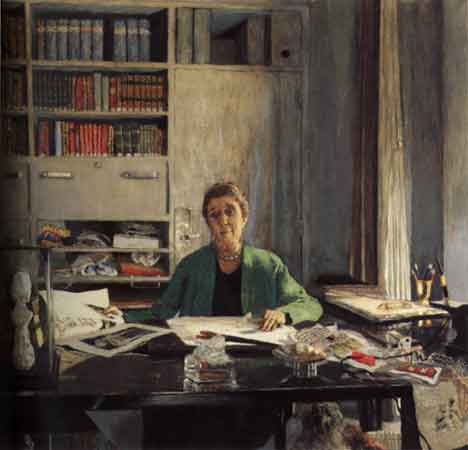

Jeanne Lanvin, 1933. Distemper on canvas, 49" x 53.7". Paris, Musée d'Orsay, Bequest of the Countess Jean de Polignac, daughter of the sitter, 1958. |

|

Vuillard in his later works has been accused

of selling out to the rich and powerful and reverting to a conservative, conventional

style, with particular reference to aristocratic settings of the 18th

century. Curiously it is a world in modern dress that seldom appears in modernist

art. There is a kind of coldness in Vuillard's approach, in his fidelity to the

office setting of an automobile manufacturer, for instance, or the pristinely

overdecorated living room of perfume baron's wife. His most modern scene is a

portrait of Jeanne Lavin, the fashion designer who achieved enormous success

in business and society. Vuillard was delighted with every aspect of the work,

all the stuff on her desk, the drawings, the bust of her daughter, the pencils

in their holder, books and fabrics on the shelves, the grid of the office design,

the dog under the desk. It suggested to him an updated and upgraded version of

his mother's dressmaking business at home. Rather than part of a biomorphic and

geometric pattern, the figure is the nucleus of an accumulation of objects in

space that have been shaped in her image, resources for and products of her imagination.

Vuillard continued to measure how much space each person takes up in the world.

Donald Goddard © 2003 |

|

The exhibition appeared from January 19 through April 20, 2003, at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. www.nga.gov/exhibitions/vuillardinfo.htm. It was scheduled to go on, in expanded form to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal, Québec, Canada, from May 15 through August 24, 2003; the Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, France, from September 23, 2003 through January 4, 2004; and the Royal Academy of Arts, London, England, from January 31 through April 18, 2004. Curator Guy Cogeval, director of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, deserves great credit for bringing together the massive documentation and number of works involved in this exhibition. |

Art Review - NYArtWorld.com - NYAW.com. All artwork is copyright of the respective owner or artist. All other material © Copyright 2015 New York Art World ®. All Rights Reserved.

New York Art World ® - Back to Top