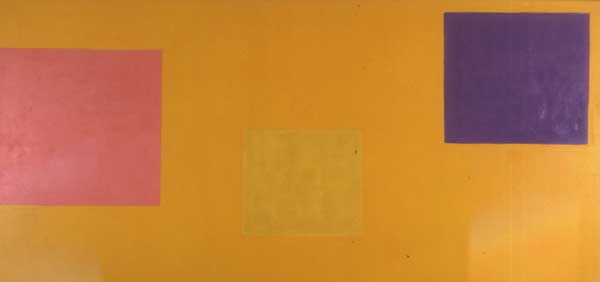

Untitled, mid-1960s. Painted wood beams.

Peter Pinchbeck (1931-2000): A Memorial ExhibitionArt Review by Donald Goddard |

|

|

For a show of Hannah Wilke's work in Berlin, the curators, Frank Wagner and Inge Taubhorn, made a series of videotapes that included interviews with Hannah's husband (me), her sister Marsie, our friend Kathy Goodell, and Marc Nochella from Hannah's gallery, Ronald Feldman. There was also a guided tour of SoHo that I did with Frank and Ingo in that summer of 2000 in which, as I remember, my energies seemed to be devoted primarily to how much the place had changed since I first knew Hannah in 1975 and even since her death in 1993. On Greene Street, across from Hannah's old loft, we ran into Peter Pinchbeck coming out of his building with a friend. I was very happy to see him for some reason. I didn't know him at all well, though Hannah and I had lived across from him for many years. We had talked on the street occasionally and had friends in common. I had never been in his loft or seen his work, except for one painting in a show curated by Barbara Rose in 1979. |

| Maybe it absolved me of my cynicism to see him now, or I was relieved that people would see that I actually knew someone. But I think my delight had more to do with Peter himself. It was peculiar that we were both still here, though he would not be around much longer (Peter died on September 3, two days after Hannah's show opened in Berlin). We stood and talked on the street, I don't remember about what, but I'm glad he was there, for me and for Hannah. Now it is time to honor him, and to continue doing so. |

© Peter Pinchbeck 2001 Isomagnetic, 1981. Oil on canvas, 96" x 192" |

| The work in this show is quite recent, from 1996 into the year of his death. There is also a notebook with published materials about him and reproductions of work he had done in the twenty years after his arrival in New York from England in 1960. In the early years he was a painter and a painter being a sculptor. He made seemingly simple constructions that invented an entirely new space while conforming to the existing one, most tellingly, for instance, using painted beams composed to fit the width and height of his loft (floor, walls, and ceiling) but that projected angles or perspectives of a third dimension which becomes as miraculous and mysterious as a fourth dimension might be. These constructions, in other words, re-created the space, went beyond the space into something that was unknown, from fact to illusion. He was, as I said, a painter, and his concerns were with expanding the universe, not with shrinking it to something understandable. In terms of Michael Friedman's idea about Frank Stella, Jules Olitski, and Kenneth Noland, Pinchbeck's support system was not the rectangle of the canvas but something much larger, more complicated, and more difficult to grasp. Pinchbeck was certainly associated with Minimalism as it evolved in the mid-1960s--he showed in the "Primary Structures" exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1965--but the content of his work was far more both extensive and inclusive than the strictures of "Minimalism" might allow. What those loft studio structures in fact contained was quite inexplicable-- cumulative and elusive. His content was "maximalist" rather that reductive. |

© Peter Pinchbeck 2001 Untitled, ca. 1995. Oil on canvas, 94" x 139" |

| And that is clear in his paintings of the 1970s and '80s, in which a few squares of bright color interact on a field of color. They derive ultimately, I guess, from Russian Suprematism or Constructivism, but their idealism, and their passionate attachment to the world, come from Van Gogh, whose work had inspired Pinchbeck to become an artist in the first place, according to Daniel Pinchbeck's moving essay about his father. Questions of "figure and ground," which devolved into cliché during the history of Minimalism and Color Field painting, actually evolved with great force as Pinchbeck's work became increasingly biomorphic. Questions of existence accompany those of abstraction. As the artist himself vigorously argued in 1980, his work is "not about geometry" (and not at all in his later work). It is not a system of notation or primarily about formal relationships of any kind, not even in the sense that those abstract relationships automatically have a spiritual dimension. It is about the mystery, or the quandary, of being. The shapes are palpable, they are not nothing or neutral, and neither are the spaces in which they appear. Between space and shape is where the painting exists. "Painterly volume is what interests me," Pinchbeck wrote in a note that is quoted in the gallery's press release. "What shapes have to have is presence, like a person, to have the reality of a figure in space, but still be abstract. I want to evoke this world, to some extent, in the rendering of form, but not in terms of the imagery. . . . Painting goes its own way. It must always evade our understanding." |

© Peter Pinchbeck 2001 Entity, 1996. Oil on canvas, 30" x 34" |

Pinchbeck's reference to a figure, a person, is interesting. Wherever we find ourselves--in landscapes, in rooms, in airplanes--most phenomena are predictable according to the limits with which we must view them, comprehensible even when we don't understand them, in other words totally unpredictable and incomprehensible. Wild animals, mountains or lightning, or even something extrasensory might be startling or beautiful but they are outside us, part of the setting in which we live, and therefore of marginal or conditional interest. The things that begin to interest and baffle us are other human beings, whom we might have reason to predict and understand but can't. |

| The contents of Pinchbeck's loft are predictable--walls, floor, ceiling, door, etc.--but the constructions he made to fit it are not. They lead us in odd directions, as though a person had entered the room and changed the equation of our settled expectations entirely. Likewise the paintings of the 1970s and '80s, in which the enormous rectangle of the painting is the total sum of space and the two or three or four squares of color create an absolutely new and unique balance and dynamic within the space, something that could never have been predicted. |

Untitled, 1996. Oil on canvas, 72" x 90" |

The squares are presences, definitive, hard-edged entities distinct from the surrounding field. There is no doubt that they are there and that they are certain dimensions and colors. And yet there is something uncertain; they are reflections or constructions, shadows in the Platonist sense, formulations that have been projected to create an ideal balance of size, shape, and color. Sly and insinuating, they propose a perfect world. But somehow it is understood that no part of this world would exist without the other parts, that they partake of one another, and that the relationships among them--their balance and correctness--are far more complicated than can be shown, or known. |

| So there is a paradox in the work of Pinchbeck's last ten years. The world is no longer perfect. There is still shape and field, figure and ground, but both are now made with layers of brushstrokes and color that push into one another and emerge out of one another. The end of space is the beginning of shape, though they are distinct from one another. Light emanates in various ways from within, unifying space and relating shapes across a distance. In a huge untitled painting of 1995, for instance, light even seems to come from a fused sun and moon figuration above to touch the darker figures below. The figures themselves are like bodies--rounded, indented, vulnerable--unlike the hard squares of the earlier work. They are truly, in Pinchbeck's words, "painterly volumes." Despite their vulnerability, ambiguity, and extreme painterliness, these "volumes" are more powerful, more real presences than ever. They are formed from the space around them, contain all the energy, including the light, of that space, and maintain the integrity (which is actually the title of a 1996 painting) of their own being in opposition to and in conjunction with that space. It is extraordinary to gaze across the surface of a painting like Integrity and to recognize at every moment, from the depths of the work itself, the coalescence of matter and spirit. Constructivism has become expressionism. The universe contains shapes that themselves contains universes. The artist is himself the presence, the source of light, the embodiment of energy. Donald Goddard © 2001 |

Art Reviews Listings - Previous Review - Next Review

Art Review - NYArtWorld.com - NYAW.com. All artwork is copyright of the respective owner or artist. All other material © Copyright 2015 New York Art World ®. All Rights Reserved.

New York Art World ® - Back To Top