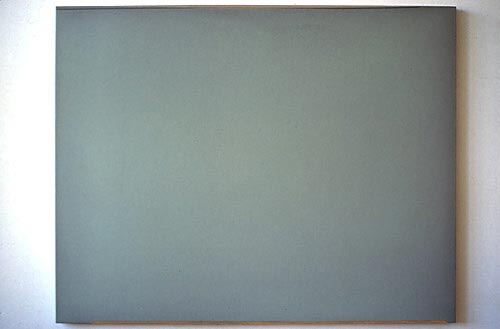

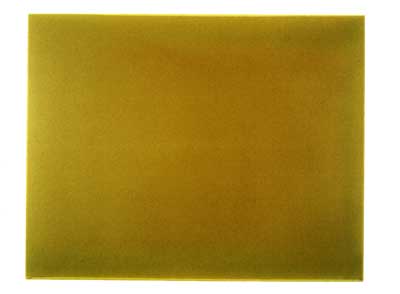

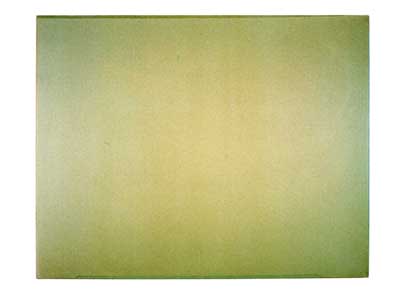

| Pihl makes no images, unlike

Jackson Pollock, who buried his under skeins of consciousness; or Ad Reinhart,

who structured his "monochrome" fields with grids, which themselves are images;

or Ellsworth Kelly and Robert Ryman, whose shapes are also images, defining spaces

apart, but of the mind or being. Pihl has eliminated images, or perhaps, as Petrea

Frid suggests in her perceptive introduction to the show's catalogue, what we

know has been blended together: ". . . , the images that surround us everyday

have been stripped of their representational noise and adherent messages so that

their essential aesthetic qualities are laid bare." In their seeming perfection,

Pihl's seductive amalgams of unnamable colors (colors that were both named and

fashionable in the 1990s) undermine those "images that indiscriminately push

aesthetic perfection in order to bypass our feelings of discomfort and alienation."

Pihl hopes for imperfection, in his words, "to allow the experience and perception

of these wounds and irregularities, as well as an intended visual tension to

surface and grow with time." |