The Secret to Making it in the Art World?

The Surprising Formula for Becoming

an Art Star:

... Study maps the galleries, museums that determine the next Picasso,

as well as the ones that don’t have as much sway

By Kelly Crow,

WSJ Nov. 8, 2018

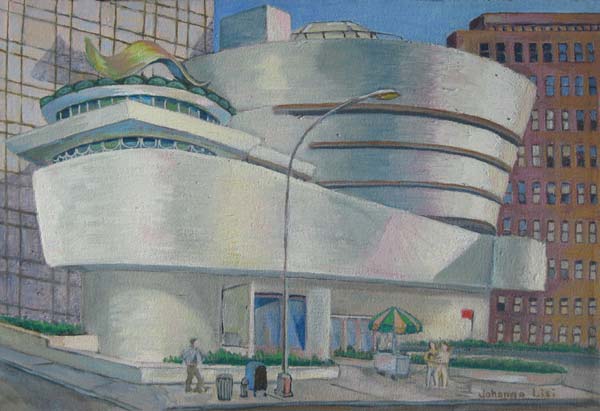

The Guggenheim Museum © Johanna

Lisi

Oil on Canvas, 12" x 16"

An early-career exhibition at museums like New York’s Guggenheim all but guarantees a successful art career, according to newly published research.

The secret to making it in the art world? Learn to schmooze.

A handful of U.S. and European museums and galleries have an outsize impact

on which contemporary artists achieve lasting, prestigious careers and

which don’t, according to a Northeastern University study published

Thursday in the journal Science.

New artists who show their work early in a relatively small network of

400 venues—like Gagosian Gallery or the Guggenheim Museum—are

all but guaranteed a successful art career, the study said. By contrast,

artists who exhibit mainly in lower-level galleries and midtier institutions

are likely to remain stuck in that orbit.

“There’s this invisible network of trust that exists in the

art world, but the group that decides who matters in art was considerably

smaller and more powerful than we expected,” said Albert-László

Barabási, a data scientist who studies networks at Northeastern

and led the study along with several colleagues including a data scientist

now at the World Bank, Samuel Fraiberger. Their findings also show up

in Dr. Barabási’s book published earlier this week, “The

Formula: The Universal Laws of Success.”

His findings undermine a popular art-world notion that a prodigy could

create in obscurity and get discovered years later. Instead, the research

suggests that artists who start out seeking connections with powerful

curators, dealers and collectors within the nerve center of the art world

are far more likely to hit the big time.

Dr. Barabási and his team spent the past three years reconstructing

the exhibition histories of nearly 500,000 artists, whose work was shown

in about 16,000 galleries and 7,500 museums between 1980 and 2016. He

and his team also scoured sales held in 1,239 global auction houses from

the same 36-year time period.

They used this data to help trace the paths that artists took early in

their careers, tracking how one who earned a spot on the roster of Gallery

A subsequently got exhibited in Museum B and then Museum C, for example.

Dr. Barabási analyzed the overlapping connections and mapped the

institutions that proved key in helping the most artists succeed in the

long run—or not.

The result is a formula Dr. Barabási said can predict which artists

working now, based on their connections within this network, are more

likely to become superstars.

“If one of your first five shows as an artist is held at a gallery

in the heart of this network, the chances of your ending your career on

the fringes is 0.2%,” Dr. Barabási said. “The network

itself will protect you because people talk to each other and trade each

other’s shows.”So who makes up the nucleus of this network?

The list skews toward U.S. institutions like the Museum of Modern Art,

the Art Institute of Chicago, the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Metropolitan

Museum of Art. European museums include the Haus der Kunst in Munich and

Tate in London. Dealers include Paula Cooper as well as galleries with

multiple locations and sizable operations like Pace Gallery, Hauser &

Wirth and David Zwirner.

Magnus Resch, an economist who teaches at Columbia University and who

helped Dr. Barabási gather the data, said he was devastated by

the findings because they suggest that myriad galleries outside this hub

have little impact, no matter the quality of the art they show or sell.

“The art world prides itself on being so open and inclusive, but

the truth is the opposite,” Mr. Resch said.

The study also maps out so-called islands on the network’s periphery,

populated by galleries and museums in places like Germany, Australia and

parts of Asia that appear insular to a fault. For example, Germany is

replete with noncollecting museums called kunsthalles that organize many

shows featuring young artists, but Dr. Barabási said his research

revealed that few of these venues wound up swapping artists with the influential

museums that ultimately determine an artist’s success.

“The conduit to bigger success isn’t there,” he said,

though he conceded there were likely exceptions.

The network also benefits artists who live in cities with thriving art

markets like New York and London. Of the artists tracked in the study

who were born in the U.S., a quarter earned spots in highly prestigious

venues, compared with 11% of artists in Canada and 9.2% of artists in

India.

The network isn’t defined solely by geography, though. Galleries

physically located near MoMA weren’t necessarily more influential

than ones in San Francisco or Shanghai, the study found. In some respects,

Dr. Barabási said it mattered more for an artist to get a show

at a major, encyclopedic museum like the Art Institute of Chicago than

a buzzy, contemporary art museum.

That’s because the Art Institute shows fewer living artists, and

so it “has more heft,” he said. So far this year, the Chicago

museum has opened shows featuring a dozen living artists. Last year, it

showed eight.

James Rondeau, director of the Art Institute, said he remains skeptical

of success metrics in the art world, but added that he wonders if the

research could nudge curators out of ruts they might be in when it comes

to scouring for talent.

“Maybe we can use it to give voice to those disenfranchised artists

outside the trajectory,” Mr. Rondeau said. “We need to use

our eyes as much as our ears.”

Write to Kelly Crow at kelly.crow@wsj.com

Reprinted from The Wall Street Journal, November 12, 2018