New York Art World - Spring Studio

SPRING STUDIO - EVENTS - NYC

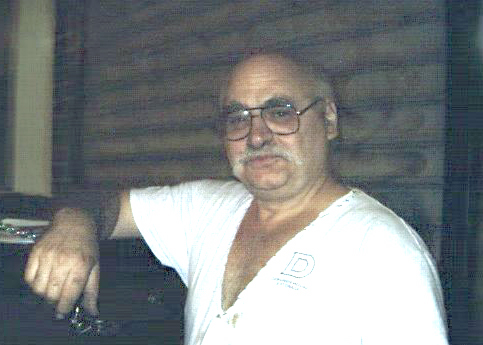

JOSEPH CATUCCIO - TO MASSACHUSETTS

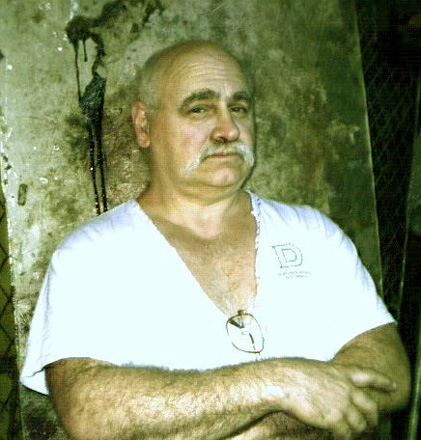

WHO: JOSEPH CATUCCIO, Draughtsman, Fine Art Painter, and Writer

WHEN: SUNDAY, July 12th

WHERE: SPRING STUDIO, NYC

WHY: JOE'S MOVING TO MASSACHUSETTS

|

JOE CATUCCIO who held figure drawing sessions at 32 Greene Street in SoHo for thirty years, but was forced out fifteen years ago and moved his "PROJECT OF LIVING ARTISTS" to Bushwick, is soon leaving town in order to relocate to Massachusetts which would be in the vicinity of his brothers and extended family. He will continue his writing, as well as his Project of Living Artists very soon after settling down in his new home. We had a great party for Joe on the eve of his moving to Massachusetts.

Minerva Durham

Below I have pasted a very old New York Times article featuring Joe when he was in SoHo. Twenty years later it is still relevant, asking important questions about artists and the making of art.

|

|

|

Becoming Artists the Old-Fashioned Way From: The New York Times "Life drawing, once the art student's

entrance ticket to the mythical world of canvas and paint, of chisel

and stone, of masterpieces scribbled feverishly on napkins, of berets,

garrets, mistresses, poverty, drugs, wine, death and, ultimately,

fame, is now an entrance to -- well, no one seems to be sure anymore,

but probably something bleak, like painting portraits of corporate

executives for a living. Certainly it is no longer an entrance to

anything very fashionable, or, in the opinion of many, artistically

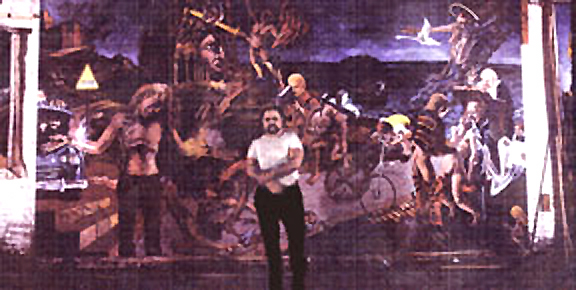

credible. The project, which is also Joe Catuccio's residence, looks like a junkyard and feels like home: the models are well treated, the artists feel comfortable and Mr. Catuccio's two cats search the floor leisurely for tidbits. A greater contrast to the pristine austerity of the typical SoHo gallery would be hard to imagine. And in fact, there is virtually no connection between the two. Life drawing, if not actually in the hell to which successive generations of abstract and conceptual artists have consigned it, is at best in limbo, filled with self-doubt and facing challenges and questions on all sides. Making Souls Visible Despite the critical success of the recent

Lucian Freud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the

current show of modern drawings at the Museum of Modern Art, this

situation seems unlikely to change. The figurative painter Philip Pearlstein, speaking recently in his Manhattan studio, recounted being sternly warned by Ad Reinhardt when they were both teachers at Brooklyn College that he would "be responsible for the souls" of all the people he painted. "He meant it," Mr. Pearlstein said with a smile. "He wasn't joking." Asked if he thought life drawing should be emphasized in art schools now, Mr. Pearlstein said: "Only if people want it. You invite all sorts of prejudices against yourself as an artist if you do it, which makes it challenging. You want to get away with it." One Who Dares Eric Fischl, one of the few younger figurative artists to have gotten away with it, made his name in the 1980's with raw, sexually charged images of suburban life in which the body, oozing suntan oil and neurosis, forcefully reclaimed center stage. Nonetheless, despite the prominence of the figure in his work, Mr. Fischl readily admits that drawing feels very much like an acquired skill, one he had to teach himself after leaving art school, where drawing wasn't taught. To some, Mr. Fischl's lack of training as a draftsman is a serious flaw; others argue that his paintings gain in power precisely because of the slapdash quality of his draftsmanship. His critics would argue that to paint in a consciously careless manner, an artist needs to know how to render a figure skillfully in the first place. Others seem to believe that in a modern context, average drawing skills are enough; what matters is the overall composition. Both sides, in different ways, evince a horror of academicism, the "beautifully" drawn or painted figure, in much the same way rock musicians disdain perfect pitch. In the modern world, graininess and rough edges convey authenticity. So where does this leave life drawing? While it might seem ludicrous for the beginner to draw expressively before knowing how to get proportions right, most schools now emphasize personal expression over systematic training. But how far should an aspiring artist go along the path of drawing well, of attaining technical mastery? In the Renaissance, the answer was simple: to the end of the path, where popes and patrons waited with handsome commissions. In 1994, even among the minority who agree on the existence of a problematic pathlike entity, just how far one should go on it is a matter of dispute. Two Extremes of Instruction Camped furthest up the path is the Graduate School of Figurative Art of the New York Academy of Art, founded on the assumption that the artistic instruction of the Renaissance and the French Academy is still valid. (Andy Warhol was one of its supporters.) At the academy, the intent is clearly that students should learn to draw well. They undergo four semesters of figure drawing, as well as cast drawing and detailed instruction in anatomy and perspective. James Lecky, the chairman of the school's master of fine arts program, said the aim was for students eventually to be able to draw figures without reference to photographs or models. Learning to do so takes time, and that, said Mr. Fischl (who has taught at the academy), is another part of the problem. "When I taught at the Nova Scotia College of Art, there were students who were included in video shows at the Museum of Modern Art," he said. "Because the medium took care of itself, they were free to ideate the way an adult could. They couldn't draw at all. That was absolutely not part of their education. The thinking was that basic skills, the fundamentals of painting and drawing, not only set you back in time and were ultimately unnecessary, but that they had a prejudice built into them that would undermine the conceptual stuff that was going on." While a student can begin producing conceptual work almost immediately, one learning to draw and paint must be resigned to some sort of apprenticeship. This is not an easy attitude to maintain today. Not only does the notion of studying to become an artist, as opposed to simply being one and acting accordingly, raise eyebrows, but there is also the small matter that this arduous apprenticeship is taking place in an art form that, in the view of most of your peers, is already dead. Actually, figuration has never been more alive, but the means for producing it are overwhelmingly mechanical. Why draw something when you can photograph it in a fraction of the time? Luke Butler, a recent graduate of Cooper Union School of Art and Design, said his ability to draw was his most precious skill as an artist. But he said the two or three months he had spent learning to draw in high school had been adequate. When he showed teachers his drawings, he said, their reaction was that of the average person on the street: "Oh, you can draw!" Prof. Paul Gianfagna, who teaches anatomy in the art department of Brooklyn College, said he regretted the current academic trend "not to instruct." He said students "tend not to be comfortable with drawing" and were left "to search vaguely for a personal style rather than using a figure-drawing class as one of several resources for developing a visual vocabulary." He added: "Instruction, the study of conventions, developing a visual vocabulary, is going to carry a student much further than a superficial discussion of style and personal exploration." In the meantime, work at the PROJECT

OF LIVING ARTISTS goes on as it has for 25 years. The artists

stare at the model; the model stares back. She earns and poses; they

pay and draw. It is a nice arrangement. In an era of channel-surfing,

it is rare to see people paying this much attention to another human

being. Life drawing may be in decline, but it is doubtful that anything

will ever kill it. As the Freud show at the Met attested, there will always be those for whom, in W. H. Auden's words, "Art's subject is the human clay, and landscape but a background to a torso." SPRING STUDIO 91 Canal Street at Eldridge St, NYC 917-375-6086 |

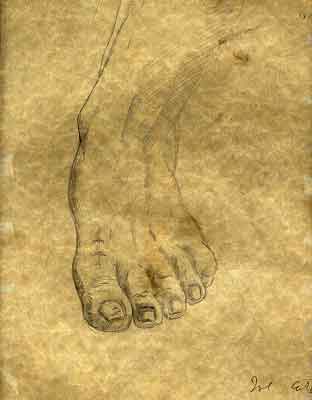

Sculpture by Joe Catuccio

The Project of Living Artists

Click Here to View More of |