| In any case, the

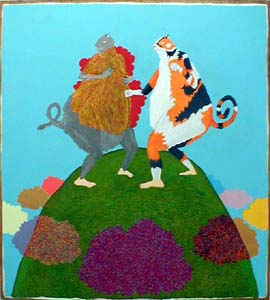

entire scene is subject to the conventions of drawing. There is nothing that

is not obviously drawn, including, of course, the drawings within the installation.

The space is a cartoon space, not as a fantasy or special world as it had been

through the generation of Keith Haring, but as an actual place from which there

is no escape. As animation, as cyberspace, as image, the world comes to the person

rather than the other way around. It is part of the body in which the person

resides. I suppose it is possible to imagine being in a commercial, a situation

comedy, or a reality show on television, but that is not the way it works. It's

the other way around, with those scenes becoming part of your life, perhaps not

the determining part, but something that holds life in stasis. This is the only

way the mind works in this situation, which currently is the situation, through

media. The person is cast back into the cartoon, which becomes a vehicle of personal

expression, as therefore does the drawing itself. Every mark--describing the

hair on legs and body, the drops of water, the shingles of the house, etc.--is

a mark of emotional identification, of being in the cartoon.

So the experience of all seven artists' work in "Were you alright

yesterday?" is always painful--funny or sad or even affectionate, but painful,

and aware of the world being thus described. Each of the young women in Rebecca

Westcott's three large paintings is said to be in that uncertain moment before

her photo is taken. Paradoxically, their alienation as subjects of media, of

photography (and painting) is balanced by their vulnerable humanity, their vividness

as characters, as figures in tension. The paint genuinely describes them and

their aliveness, not something about their station in life.

In very different ways, each of the other five artists

embodies a consciousness that is extraordinarily sensitive to the hand and conscience

of the artist. Nils Carstens' medium is delicate, fine-lined illustrational drawing,

through which the reveries of nubile young female figures and children are effortlessly

and somewhat subliminally intersected by processions of more ominous male imagery:

tanks, submarines, and in three large drawings by the intrusion of male hands,

perhaps those of the artist, manipulating the face of a beautiful adolescent

girl as though to force feeling or to discover the reason for its beauty. In

the latter series, there is a kind of violation that nonetheless cannot overcome

the emotional integrity of the face itself and the life of which it is a part. |