|

© Anita Steckel

Giant Woman Over New York,

1972-73.

Photo montage and drawing, 3' x 4

|

© Anita Steckel

The Subway,

1973.

Photo montage and drawing,

3' x 4'

|

© Anita Steckel

Fashion,

1962.

Oil on photo.

|

© Anita Steckel

Creation Revisited

1976.

24 xeroxes,

6' x 3'.

Detail, 8 1/2" x 14"

|

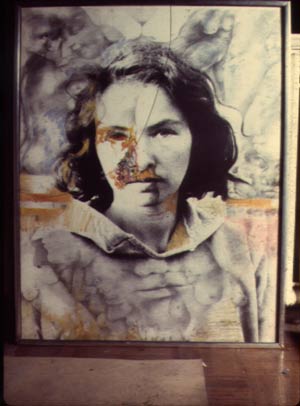

The Big Rip-up,

1964.

Drawing and painting on photo.

Because we see through our own eyes and in our own minds we are always in the space we are looking at. So nothing can be objectified. What exists ranges between being too knowable and not being knowable at all. One rock might appear to be something quite different from one rock placed on top of another rock. Cities are combinations like this, perhaps more complicated, perhaps not. The products of people are obdurate, just like everything else, only subject to more explanation.

Anita Steckel knows this obduracy and deals with it in a very particular way. It is not so easy to move things that exist, to change them, to transform them. However one might try to avoid them, they are still there: city, religion, sexism, nationalism, fascism, fashion. Everywhere we turn are images that define the way things are, or that automatically trigger certain channels of thought and behavior. It is this constricted space in which Steckel works, confronting or coexisting with Madonna and Child, New York cityscape, Michelangelo's Creation of Adam, men on a New York City subway, a monument to the German state, the Venus de Milo, old portraits of people, Leonardo's The Last Supper, photos of tribal life in New Guinea, etc. And the spaces become hers. She occupies them just as surely as their images occupy our consciences, either through her own self-image or her intrusion of other images. In a direct and often outspoken way, the work of art becomes a place where image, artist, and viewer are one.

The technique Steckel often uses originated with collage in the second decade of the 20th century, and more specifically with the montages (purposely combining fragmented photographs, typography, and drawing) of artists like Hannah Hoch and John Heartfield, whose work was profoundly political in the years leading up to and into Nazism in Germany, and Max Ernst, who created hybrid Surrealist narratives. Her concern, however, is not so much with identifying the pathology of human behavior as with invading and claiming a place that would exclude her (and us). It is an exclusion that usually has political, cultural, or social roots, but which has become over time ontological. In the "Giant Woman Series" of 1972-73, when Steckel draws a nude figure of herself holding a paintbrush and straddling the Empire State Building high over New York City, she is claiming victory over a phallocratic structure for women and for herself as an artist but also claiming the importance of her own presence and questioning assumptions about hardness, rigidity, and regimentation in contrast with humor and sensuality. In other words, any assumption is liable to contradiction by the experience of a single person. By placing her own nearly nude figure between two men, one younger, one older, seated in a subway car, Steckel is not simply ridiculing by contrast; she is changing the equation of relational possibilities in the larger world of emotion.

Steckel intrudes in time and space. In the late 1950s she made self-portraits of great clarity and directness that seem to emerge from early Netherlandish and German painting of the 15th century. Her montages of the early 1960s rectified or readjusted old photographs and matted them in old-fashioned book endpapers. Her method was not to cut and recombine as in most montages, but to actually alter the image by, for instance, turning a boy into a young Hitler by painting a mustache and bangs on his face (The Beginner) or by giving a fashionably dressed (for the time) woman two heads, one on top of the other (Fashion). The endpaper mattes are not gratuitously decorative but pprovide a context for the images, for instance, the double bird (double eagle) pattern around The Beginner and the feather-like repetitions around Look at the Birdie, which features a winged figure of Death. The patterns are like inescapable integers of history and time. As in the later "Giant Women" montages, Steckel enters here precincts here that are presumably off-limits in terms of how we fool ourselves about meaning, or about life in general.

Out of the "Giant Women" series came another series called The Journey, which originally had 48 8 1/2" by 14" Xerox sheets in a grid and subsequently was reconfigured in 24 sheets for the 1976 feminist exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. The original work began with the image of the Giant Woman Over New York, and Steckel's nude self-image then "flew" over the Atlantic Ocean and through Europe to the Vatican, where it entered the Sistine Chapel to join Michelangelo's ceiling fresco of The Creation of Adam. In each panel, Steckel moved the paper around in the Xerox machine to blur the images and make her body appear to fly. The effect is strange in that Steckel's figure seems intent on liberating Adam from the grip of his relationship to God the Father and to the decorative and theological scheme of this all-male enclave. The smaller work of 24 panels, which has only the final destination in the Sistine Chapel, is called Creation Revisited.

"The Tribe," a series of photo montages of the late 1980s, takes the artist even farther away, to the Asmat people in the forests of New Guinea. She is there, as she is everywhere, a naked odalisque, a face, but also an artist, not simply an observer, of masks, painted bodies, and handprints that signify the outer reaches of actually knowing. There is a resolution here of some kind between mind and body which becomes even more pronounced in Steckel's "Amagansett Series" of the 1990s, which merges photos of herself and others in double exposures with fields of flowers. This is a reversal of an extraordinary early self-portrait called The Big Rip-up (1964), in which the artist's photographed head and torso are surrounded by and nearly submerged in her drawings of male and female heads and naked bodies. Bright colors spout from her right eye and down her face as though her feelings and sorrow were identified with the brilliant chaos of her art. It is the eye again, the eye through which she (and we) see, and at its center is the crotch of a drawn female body. The colors cascading from this convergence describe almost impossibly small bodies. Nothing is so small that it is not there.

Donald Goddard © 2001