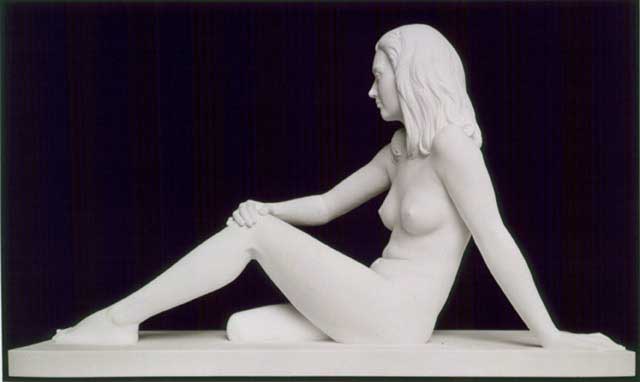

Selma Mustajbasic, 2000.

Marble,

35" x 22" x 57".

Marc Quinn: The Complete Marblesby Donald Goddard |

|

Selma Mustajbasic, 2000. Marble, 35" x 22" x 57". |

Some of E.M. Forster's characters went from England to Italy to live in villas and walk the countryside, to immerse themselves in a different culture. Marc Quinn's went as body casts to be carved in marble by Italian craftsmen, also to be immersed, to be engulfed within a particular form and shape of human history. There were eleven life-size portrait sculptures in the show, of Helen Smith, Alexandra Westmoquette, Catherine Long, Selma Mustajbasic, Alison Lapper (eight months pregnant), Tom Yendell, Stuart Penn, Peter Hull, Jamie Gillespie, Alison Lapper and her son Parys, and a young man and woman kissing. The marble is white and completely unblemished, beautifully carved in a tradition that has continued since the early Renaissance, and that had emerged centuries before in ancient Greece. It is the quintessential expression of the western classical heritage. The people are mostly young, some stout, some thin, all missing one limb or more, from birth or because of an accident, all naked. The marble doesn't notice the missing or distorted limbs, hands, and feet; it simply smoothes them over, like bark over a missing branch, or the figure of Daphne transforming into a laurel tree to escape the advances of Apollo in Bernini's Apollo and Daphne of the 17th century. |

| Many of Bernini's figures are life-size too, as though to elicit our sympathy and identification. In Quinn's figures, however, there is no theatricality, no gaping mouths or wild eyes, though Stuart Penn kicks his shortened right leg out and clenches his right fist like an Olympic kick-boxer. But the others sit or stand calmly, quietly commanding the space they occupy. Bernini operates in a rush of linear energy towards climax. Quinn would seem to typify a kind of post-modern coldness, in the locution of current art discourse. The subjects are victims or marginal, perversely the opposite of what the heroic mode would call for, unless, of course, the victims could be shown to have overcome their handicaps. They are presented as beautiful compositions or arrangements of limpid lines and graceful volumes, art constructs. The medium itself is one of great coolness and luxurious materiality (or kitsch), appropriated from tradition (cynically, by implication) in attendance with humanistic idealism (or insufferable idealizing). And, anyway, all the work was jobbed out to craftsmen. Making money, making art, on peoples' misfortunes. |

Kiss, 2002. Marble, 69" x 25" x 24". |

How curiously all that devolves. Someone suggested that the people here are too attractive and the deformities too palatable for the work to have much affect, which would seem to say that Quinn has either not been courageous enough or exploitative enough, as though his subjects belonged to some special category of humanity. So why were the casts sent to Italy? Nudity has not been a prominent feature of English art over time, except in the work of John Flaxman and William Blake around the turn of the 19th century and in the more recent paintings of Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon, to whose wonderfully sinuous figures Quinn seems to pay homage. In a way the casts were sent so they could be nude, so they could be in a warmer climate. It is hard to imagine them the same way had they been carved in England, even if the marble had been imported from Italy, or even if it had been the artist himself who had carved them. They belong in the sun, in the heart of western civilization, in the hands of people who are perfectly skilled at carving marble into human form. They celebrate those things as part of the possibilities of an English sculptor's life. They are votive figures celebrating the gift of life itself, for as long as the marble will last, even as it deteriorates over time. |

| In the exhibition, four male figures spaced out on the right

face four female figures on the left. Alison Lapper appears twice, between the

two rows, at the far end a single figure eight months pregnant, at the near end

holding her new baby Parys, who appears to be physically normal, though I honestly

didn't think to confirm that. In the lobby is Kiss, in which a young man and

woman embrace. Moving around this latter piece, I have never been so aware of

the infinite evolution of form and space, in time: the arc of his back flowing

into the fall of her hair, their four feet forming an endless variety of interlocking

angles and rectangles, the spaces between their legs and their torsos opening

and closing in the most beautiful shapes, as though stretched across the universe.

For each of the twelve figures, life forces have been poured into eternal forms,

all connected to one another, all connected to us.

Donald Goddard © 2004 |

Art Reviews Listings - Previous Review - Next Review

Art Review - NYArtWorld.com - NYAW.com. All artwork is copyright of the respective owner or artist. All other material © Copyright 2015 New York Art World ®. All Rights Reserved.

New York Art World ® - Back to Top