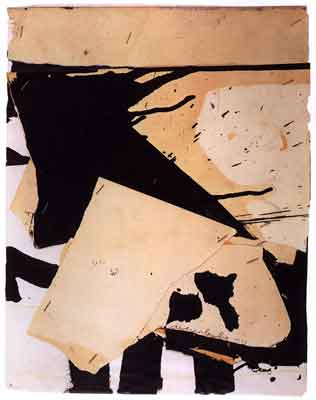

| Many of the works, large and

small, are configured in quadrants, as though to satisfy the four sides of the

rectangle, the four sides being taken as points of view, just as the figures

in the later portraits combine face-on perspectives at four different levels.

In Yellow Third, the quadrants partake of the shape of the canvas, but

they also more aggressively interpenetrate and claim the canvas, the black by

extending downward in columns to the bottom border and leftward through the yellow

to the left border. The yellow splatters and drips into the right lower quadrant

as the black does into the left lower quadrant. The work is alive, it breathes,

the shapes jostle and fill out the space. Blue appears underneath at the interstices

of black and yellow and yellow and yellow, but it is hard to know how extensive

the blue might be; it also appears dripping into the lower right quadrant. There

is no end of questions and speculations about what is going on, though one immediately

accepts the structure that is given. It is like a mathematical formula that one

has elegantly arrived at through experience.

Several paintings are literally in quadrants, four canvases

joined in a grid. Each of these is one picture, but we are compelled to notice

that there are four units, which are read as both separate and connected. They

are pictures of becoming, in which the beginning is also the end. Any one of

the four in Quartet #1 might be admired individually, but it would be

like considering only one of the four corners of the earth without even knowing

about the other three. The upper left quadrant is an intense combination of dark

green, blue, yellow, and white. The upper right is predominantly a field of white,

with tints of blue and red and the yellow shape attenuated into it. One of the

yellow arms extends down through the white into the light blue field of the lower

right, which in turn pushes into the green of the lower left, which connects

finally with the green of the upper left and is sprinkled with drips from the

yellow shape there. This implies a constant circularity when in fact the forces

are more evidently upward, downward, and lateral. So the circularity is figurative,

for the time it exists, or the time we are paying attention to it. But it is

as real as the cycles of days and nights. All of Leslie's large paintings of

this period seem to reflect the forces of nature, of growth, movement, and evolution,

of atmosphere, light, and reflection, of storm and calm. And they appear in the

colors of nature, especially in greens, browns, blues, yellows, whites, and blacks,

all inflected with other colors. |