This is not strictly a mental or aesthetic,

that is to say "abstract," process, but one that is crucially and inevitably

visual, concerned with visual reality). De Kooning is above all a visual (intellectual)

artist. What he sees - bodies, parts of bodies, shadows, chairs, windows, letters,

etc. - enters into an arrangement that belongs to him, but also to the world.

There is nothing that has not entered this way. If you look at a knee, everything

else around it changes, as then so does the knee. Rectangles are not just rectangles

but windows or spaces between chairs and legs. Real objects are constantly hitting

the eye, as though we were in a moving car. The principle of organization is

in the drawing or painting. Eventually, as Hess pointed out, the shapes de Kooning

has confronted, along with lines, colors, and brushstrokes, become part of a

vocabulary with which the artist struggles to make something that is incoherently

coherent, that is real. The degree of abstraction is perhaps confusing, but,

despite the artist's discovery of "no-environment," his specificity of place

and of form is far greater than in any Cubist work.

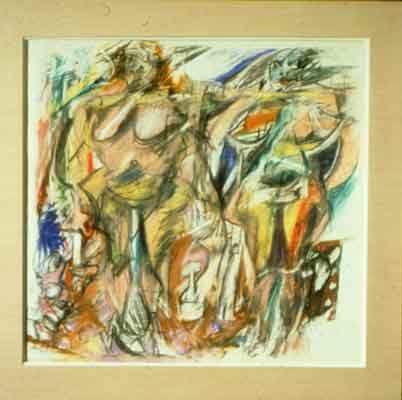

But rather quickly place drops away and we are

faced with woman herself, her flesh and mouth and vagina and breasts, far more

than we ever have been in the past, even in Rembrandt or Manet or Picasso, not

least because everything is active and clashing. It is part of our reality, not

some other mythological or voyeuristic reality. Sexuality becomes increasingly

insistent from 1950 on. The women themselves expand to fill the surface. Breasts,

hips, and eyes expand. Faces become more masklike and, in drawings such as Two

Women of 1951, almost disappear. Marilyn Monroe makes a brief appearance,

as do mouths of women cut from magazines and pasted on to de Kooning's drawn

or painted faces. Now these humans have fully become creatures of the artist's

(very fast and very commandeering) movements of line and paint. In the guise

of billboard bombshells, they are like ancient deities, as de Kooning sometimes

thought of them, staring at us from the deep past.

Perhaps too deep in the past. Eventually, paint

itself takes over, as can be seen in several passages of Two Women with Still

Life of 1952, and particularly in the single figures like Woman (Blue

Eyes) of 1953. His landscape-like abstractions of the late 1950s are totally

composed of brushstrokes, and women, for the moment, disappear. But not for long.

When the artist moved from New York City to the country (Easthampton at the end

of Long Island), they re-emerged in a new place and a new light.

I don't know why the subtitle "Tracing the Figure"

was used. To emphasize that de Kooning was a figurative painter, I suppose, in

this age of computable figuration. He did do drawings on tracing paper, a couple

of which are included in this show, sometimes to try out ideas, but the implication

of tracing figures is misleading. The exhibition itself, however, is extraordinary.

Donald Goddard © 2001

|