Audubon's Aviary

by Donald Goddard

Leach's Storm Petrel (Oceanodroma leucorhoa). (Detail)

Audubon's Aviaryby Donald Goddard |

Leach's Storm Petrel (Oceanodroma leucorhoa). (Detail) |

|

Birds are the most perfectly designed of all creatures--of all living organisms. There are about 9,000 species of them in the world (less than fish, more than mammals, amphibians, or reptiles), and most of them are quite distinct in their markings. They can be dull in color, but most are startlingly bright, original, reflective, and sometimes iridescent. Their beaks vary enormously, from ponderous hooked affairs to long, narrow needles, and their body shapes are equally diverse. The needs of flying, diving, soaring, and sitting in a cold wind or on a nest of eggs are well provided for by feathers of several varieties and gradations for the wings, of rudder-capable length for the tail, and of warm thickness and softness for the chest and lower body. When they fly, all these characteristics mingle in the most amazing patterns. More completely than other animals or plants they encompass the four elements--earth, air, water, and fire (reflectively, kaleidoscopically) -- and they are seen almost everywhere in the world. |

|

For John James Audubon, the birds he saw in

the wild, and those he killed and wired as models, were the exact equivalents

of his materials and imagination as an artist. The birds came to exist on both

sides of the grids he made, eliminating the distance between subject and object,

occupying their own space in a way that is precisely comparable to the brushstrokes,

lines, and colors he used to record them. He wanted to portray every bird species

in North America and managed to do perhaps half of them in the 435 hand-colored

aquatint engravings, based on his original watercolors, that comprise The

Birds of America. Born in Haiti in 1785, he grew up in France, was sent to

Pennsylvania in 1803 to avoid Napoleonic conscription, married there, moved to

Louisville, Cincinnati, and New Orleans to earn a living, and increasingly took

long excursions on foot--through the Mississippi River Valley, Florida, Labrador

and other parts of Canada, the Upper Missouri River--to answer his obsession

as an artist, which in his case encompasses naturalist. Unable to arouse interest

for publication in Philadelphia in 1824, he was more successful in Edinburgh

and then London, where he voyaged for several long stays between 1826 and 1837,

while The Birds of America was engraved in elephant (oversized) folios

so that even the largest birds could be portrayed life-size. Eventually, subscribers

to this unique publication numbered 79 in England and 82 in the United States.

|

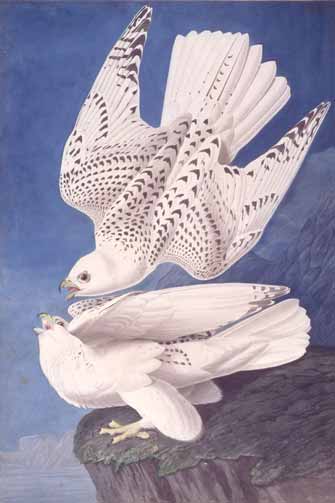

Gyrfalcon (Falco rusticolus linnaeus), 1837. Havell plate no. 366. Watercolor, graphite, pastel, charcoal, and gouache with scratching out and touches of glazing on paper, laid on thin board. |

Gyrfalcon of about 1835-36 depicts two birds in the white phase of this rare species from the Arctic. How dry and unworthy any such description of these living creatures, and of Audubon's perception of them. In fact, the two birds, one flying, the other crouched in determined reaction, dominate the space not only of the picture but of the vast barrenness of the precipitous ledge, the mountains, and the sky. The flying bird fills the upper half, with its wings and tail spread and its wing tips touching the top and right sides. Dark gray markings, shaped like birds in flight, spread across the flying bird's back and wings in a pattern like a flock of birds, miraculously reinforcing the movement of the single bird. The composition is defined by these surface patterns and the incredibly clear outlines of both birds that fill the space, by their movement and the force of life. The crouching bird cradles these movements like the base of a column. Even more locked in, to the composition, each other, and the North Atlantic Ocean around them, are the two birds in Leach's Storm Petrel, of 1831 or later. In eccentric flight, tossed by the wind, they are seen one from underneath, the other from above, and thus described perfectly for ornithological purposes. The negative spaces between the birds, wings and tails, wings and water, bind them together in perfect consonance with the wave of water that sweeps up to the right. The animals are wedded to their environment, as they are naturally, and as they are through the will of the artist. |

Leach's Storm Petrel (Oceanodroma leucorhoa). Havell plate no. 101. Watercolor, pastel, black ink, gouache, and graphite with selective glazes on paper, laid on thin board. |

Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis), ca. 1825. Havell plate no. 26. Watercolor, graphite, pastel, gouache, and black ink with scratching out and selective glazing on paper, laid on thin board. |

The seven birds in Carolina Parakeet of about 1825 suggest the abundance of this species in the southern United States during Audubon's early years. Even then they were diminishing, and by 1920 they were extinct, as Passenger Pigeons had become extinct in 1914. Perhaps the great numbers of both species, which Audubon experienced and described, inspired people to slaughter them in a very short time. Perhaps his aesthetic included the urgency to preserve them. Here the parakeets populate a Common Cocklebur in their typically boisterous way, stretching their wings, balancing, grasping, reaching, and squawking. And the Cocklebur sends out its branches and burrs in various diagonal directions so the birds can do all that. The symbioses of use, line, shape, color, and wildness are intimately understood, as the birds wind down through the grid of the branch in a backward S-curve and the light reflects off their feathers in a myriad of ways. |

|

|

Only one human figure appears in Audubon's work, and it is a tiny depiction of himself, with a dead Golden Eagle strapped to his back, crawling across a dead, uprooted tree trunk that straddles a deep crevice high in the mountains. It appears sketchily in the lower left of Golden Eagle (early 1833), though it was not included in the engraved version. A living Golden Eagle gripping a dead Northern Hare and beginning its flight almost completely fills the foreground. It is the deepest and darkest of Audubon's subjects. The dark browns and golds of the eagle's massive shape contrast with the stark white of the hare and the frangible, chalky blues and whites of the sky. The feathers of the wings and neck seem carved like diamonds to reveal light facets in the darkness. In this girdled figure, more than any other in Audubon's work, the brushwork equals the individual strands, patterns, and textures of the bird's feathers, the glint of its eye and pilled skin of its legs and feet--its physical presence in the world. Strangely, around where the eagle's claw pierces the hare's eye, the soft, dark feathers of the eagle's legs and belly come together with the hare's white fur. The artist, crawling on his log, carrying his prey on his back, is complicit in this world, but only in a minor role. Donald Goddard © 2005 |

| The Society began last year to show on a rotating basis the original watercolors for Audubon's The Birds of America, all of which they own. Over a ten-year period, all 435 works are to be exhibited, including the 41 that are being shown this year along with works by other artists and various artifacts pertinent to Audubon's life and work. The exhibition was at the New-York Historical Society, 170 Central Park West, New York, NY 10024. |

Art Reviews Listings - Previous Review - Next Review

Art Review - NYArtWorld.com - NYAW.com. All artwork is copyright of the respective owner or artist. All other material © Copyright 2015 New York Art World ®. All Rights Reserved.

New York Art World ® - Back to Top