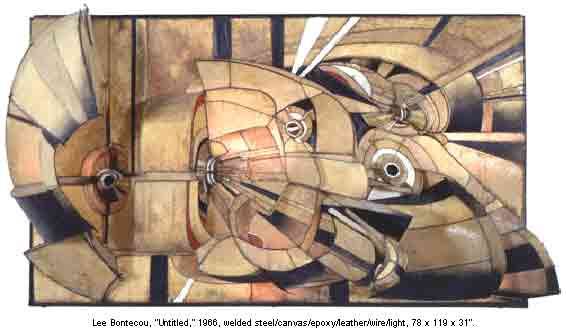

Lee Bontecou, "Untitled," 1966,

welded steel/canvas/epoxy/leather/wire/light, 78" x 119" x 31"

The Art Institute of Chicago; Gift of the Society for Contemporary Art

Lee Bontecou: A RetrospectiveArt Review by Donald Goddard |

| I know one is expected to make distinctions among the various works of an artist, that some are more successful than others. But in Lee Bontecou's case, and probably in most cases, it's beside the point. The work as a whole is a continuum, and each work along the way is a point in the continuum that contains the past and the future, neither of which exists except as the present. |

|

The Art Institute of Chicago; Gift of the Society for Contemporary Art |

|

In this retrospective there are two drawings of 1958 that seem to represent a beginning, drawings in soot produced by oxyacetylene torch, which Bontecou used for welding, with the oxygen supply turned down. As both Mona Hadler and Donna De Salvo quote her in their catalogue essays, "Getting the black . . . opened everything up. I had to find a way of harnessing it." Her sculpture up to then, done in Italy while she was on a Fulbright grant from 1956 to 1958, was figurative and somewhat like Giacometti's, or perhaps more evocatively like Giambologna's birds of the 16th century. One of the 1958 drawings is vertical, with an ovoid shape surmounting several upward strokes, like a flame or an organic figure, plant or animal. The other is horizontal and has several horizontal bands, mostly dark, one cloudy white, like a landscape. They are both very mysterious and definitive statements about the nature, or unknowableness, of things. At about the same time she did other drawings, also in soot, that seem to be about knowableness, about the structure of interwoven strands that tie everything together almost convulsively, sometimes around larger and smaller spaces of white blankness or against general darkness that ultimately suggests something beyond, or perhaps within, the structure. There followed, from 1959 through 1966, an extraordinary outpouring of sculpture (and drawing). She welded together armatures of steel rods, over which she stretched sections of canvas stitched with wire to the rods. They are like old airplanes, paintings that literally extend Cubist constructivism into space, skeletons covered with flesh and skin, and every aspect of composition, of radiating and concentric lines, is oriented around one or more circles revealing unfathomable blackness or the ominous teeth of a saw or bars of a cage. They are primary objects, as Donald Judd--in a 1965 essay reprinted in the catalogue--famously understood them to be: "The image is an object, a grim, abyssal one," he even recognized, but Joseph Cornell, whom Bontecou met in 1962, understood more, perhaps, about the range of Bontecou's concerns when he wrote in his diary about her "warnings." The warnings, and Bontecou's anger, were about human conflict, about the terrible struggles in Africa, the Cold War, the war in Vietnam, and they are everywhere in her work, those already mentioned and others suggesting modern weapons, planes, and pilots' gear, in fact gear of all kinds, as though the world could be assembled and reassembled this way, precisely what civilization intends. In 1966, there was a change. Her mounted wall pieces were still enormous and made with welded steel rods, wire, and stretched canvas and other fabrics. The holes are now sometimes white and color enters strikingly, particularly white, gold, red, and silver, along with black--royal colors. The great shapes curve and billow like sails or shells. They have an alimentary or respiratory quality and the holes are for breathing or eating or defecating, for life entering or leaving--forms seem to fill with air. The jagged sutures, unbearable darkness, and terrible violence of her recent work are overwhelmed by larger forces that belong to the sky and sea. Likewise, her drawings are of sail-like images that careen and swirl through space. This primordial world, closely observed, encompassing the earlier threatening world, is where Bontecou has remained in her art since. |

|

|

Issuing from these baroque confabulations are singular figures that suggest early forms of life. First are lyre-shaped figures of 1967 that have the symmetrical, segmented exoskeletons of Paleozoic trilobites, made much like the earlier monumental wall pieces with ribs and stretched fabric, only now the ribs are balsa wood rather than steel and the fabric is silk rather than canvas. Unlike the earlier structures, these have an incredible lightness of being, and, in fact, two of them are hung by wires within delicate, three-dimensional frames. In the same year, Bontecou began to use vacuum-formed plastic to create strange, transparent, upright flower forms, often with long thick stems, petals like the blades of a fan, and tendrils dropping from the stamen like electrical wires. |

| And in 1969-70, she produced a series of fish figures in the same kind of yellowing plastic, some up to five feet in length. These too hang from the ceiling, and all of them are composed of beautifully articulated plates that have been snapped together with grommets to form the fish. The drawings in this period are often of the same figures, drawn in white charcoal on black paper so that the flowers or fish seem to emerge in light out of the darkness. What was once desperately confrontational and disturbing now, though still disturbing, simply partakes of the ether in which we all exist. |

Lee Bontecou, "Untitled" 1998, welded steel/porcealin/wire

mesh/ canvas, wire, 7 x 8 x 6'.

Lee Bontecou, "Untitled" 1998, welded steel/porcealin/wire

mesh/ canvas, wire, 7 x 8 x 6'. |

Only two works in the show date from between 1972 and 1982, although some larger pieces were begun in 1980, but from 1982 on there is an extraordinary range of images and objects that seems to start with drawings of deluge in which sea and sky are forcefully united, great waves reaching up into space to surround the sun. It appears to be a sudden eruption of nature whose suddenness is perpetual and within which are the beginnings of more eruptions: the great force that pushes up from below bursts the bounds of heaven, now more explicitly than Bontecou's 1958 drawing in soot. There are drawings of eyes--human eyes, bird's eyes, eyes of unknown creatures, some of them evoking wildness in a way that forces us to reevaluate our own eyes and what they see. And there are eyes at the centers of enormous constructions that hang from the ceiling and hover like great spaceships, with hundreds of other smaller eyes made of ceramics, and steel rods, canvas, and wire, many of the same materials and techniques Bontecou used in her early work, only differently arranged and thought about. |

|

In a drawing on black paper of 1997, there appears

to be a window through which are seen a barren tree in the foreground, vague

hills in the distance, the moon and other astral bodies above and perhaps within,

a reddish glow that is strongest on the left, and then lights coming from some

composite configurations, like many Bontecou has happened upon before, that seem

to have wings and eyes and bodies, ambiguously natural and constructed. But the

window is not really a window; it is a frame, and the tree is on this side of

the frame as are some small elements of the configuration on the right. The tree

is in our space, along with a little bit of the rest and Bontecou's signature

on the lower right, and it comforts us. It is simply the way the world is, more

than ever threatened and threatening, in our minds and out there linked but much

larger than our comprehension.

Donald Goddard © 2004 |

Art Review - NYArtWorld.com - NYAW.com. All artwork is copyright of the respective owner or artist. All other material © Copyright 2015 New York Art World ®. All Rights Reserved.

New York Art World ® - Back to Top