©

Barry Sigel and Jeff Way

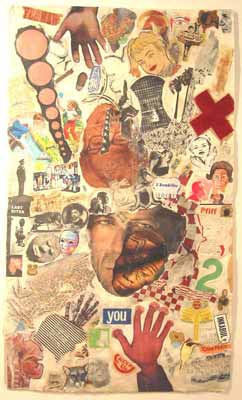

Three Bombillas

Collage

48" x 32"

|

|

Three artists among whose work there are some curious concordances, perhaps simply a function of seeing them exhibited together. Two of the artists, Sigel and Way, actually did collaborate on several collages, adding and taking away cut-out images as the work was passed back and forth between them, but here, contrarily, it is clear that two different sensibilities are present, that concordance is adumbrated by separate, if not contradictory, identities, as in two people occupying a single apartment or a single conversation, Sigel more jagged and insistent, Way more rounded and inclusive. Themes, or at least formal correspondences, emerge in some of these. Giant Hoagie, for instance, has a number of circular shapes and sexual references, and Glenn W. Turner Speaks Out has worded images, like the title and "PARTY NEW YEAR'S EVE," bracketing heads of Van Gogh, Saddam Hussein, George W. Bush, and others that indicate a level of assertive madness. In any case, the collages seem to reflect the randomness of consciousness as it interacts, purposefully or helplessly, with the world outside itself. |

|

The collages have precedent in the Surrealist practice of "exquisite corpse" drawings, in which each of a succession of participants continues the previous participant's drawing without knowing what it is (because it has been folded under), thus creating an unexpected, putatively more authentic, "irrational" imagery. Sigel's and Way's collages are more like jazz compositions in which the images must live together in plain view in the same structure. There is a constant jostling for space, representing not compromise but the acceptance of impossible juxtapositions, though neither is it possible to know at this point what has been covered up. In 3 Bombillas, all the images veer toward the center (the hands reaching up from the bottom, for instance), but most particularly from the top down--another hand that reaches down, the series of diminishing circles that points inward and down--so that everything in the upper half seems to erupt from, or to bear down on, Bruce Willis's head, including the three lightbulbs ("3 Bombillas") hovering above him. This head was apparently the first image to be pasted down (by Sigel) and it remains the focus of movement in space and the measure of time, of life and death, represented by fragments from different eras, especially the decorated face imposed on his; the two small masks to the left, reflecting his own mask; the skeletal hand and anatomized head below; and the sentinel figure on the left standing above the words "LAST RITES." |

© Jesse Reece. Three glass vessels, the tallest about 15" high, 1992. |

|

|

But there is another kind of concordance among the three artists that has to do with the mutability of their forms and images. In the collages a constant shifting of shape, form, composition, and meaning occurs as each new element is introduced. The shifting field encompasses all its shifts when the final addition is made, but still it is perceived as shifting, still in play. Jesse Reece works in a medium that literally shifts, or is shifted. Molten glass is blown into shapes that then harden but retain the fluidity of their moltenness. Reece's shapes sometimes nod and gesture like animals. Others, particularly those in clear, uncolored glass, seem to contain within their shapes the reflections of objects, surfaces, and patterns around them, like a mirror, but one that has captured those qualities and made them part of its own substance. Rather than hold a mirror up to nature, as the traditional formulation goes, he fashions the mirror to interrogate and reform visual reality.

|

|

|

Jeff Way's work depends on an impossibility of preventing the collusion of forms and images. Every idea, shape, image, color, or person is part of other such phenomena, especially for an artist, who has to contrive some visual coherence out of what is in his own conscience. Most directly, Way did a number of woodcuts combining faces of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in such a manner that they cannot be separated. In a series of pastels, the heads of Dutch Neoplastic artists of the 1920s--Mondrian, Vantongerloo, and Van Doesburg--are fused together in various ways within arrangements of geometric color shapes. So it is that modernist, and modern, phenomena appear to us with a single face, but one that is, acknowledging our modernist sensibility, made up of many facets. In another series (of acrylics on plexiglas), figures from Bebop jazz of the 1940s and '50s--Charlie Parker and Dizzie Gillespie--are associated with artists of the Bauhaus, the art school that was closed by Hitler, in the context of their measured structures. Some of these express an anger that pervades the Jekyll-Hyde woodcuts as well, but they also make an extraordinary leap of intuition between the two movements and among their participants. |

|

|

One wall and part of another is covered with masks that Way has made over the years. If the other works represent modes of understanding, complicating conflations of good and evil, music and architecture, artists and their art, the masks are expressions of power, as they always have been. They are, in a sense, means of overcoming the ambiguities of understanding, behind which can be exercised the energy of one's being, in dancing, chanting, acting. The movement of time, of history, comes to rest in the mask, which pushes back against time and history. Way created the "Grid Heads" by making xeroxes of a mask as it was being manipulated on the machine, then adding oil pastel to the resulting wavy patterns. The mask itself forms a force field, a distorted grid that might once have served to plot images but rather now takes over the space. The mask is the plotted image. Images seem to invade the spaces of Sigel's work as well. It's not that the images are hyper-real, that is, depicted with great attention to detail, but that they are hyper-insistent. A group of whale-watching boats bunches in a tangle of hulls and masts. They float together on the paper as they do in the water. A water tower in southern New Jersey dwarfs the houses at its base and obliterates the sky. A lighthouse in a similar screenprint is repeated three times, as though once were not enough. In Christopher Street Christ, we are dwarfed by the image of a crucified Christ, which rises above us and is connected to every groin vault in the church, creating an inescapable web. Our attention is commanded by objects and ideas to which we might have no immediate relation, except that they have slid into view and represent a suddenly powerful vision of the world. |

© Barry Sigel Blue Still Life, 2004 Screenprint 30" x 22" |

|

Much of what Sigel does is accompanied by mistakes and accidents, in the sense that everything is there by accident--boats, lighthouses, crucifixions--and that his process of forming images and pictures parallels the accidental nature of the world we experience every day. Everything in the world is useful to us, or at least we have learned to fit everything into our concept of a useful world. But what is it when it is not being useful, when it is in the mode of having no particular meaning in our lives--that is, most of the time. Then we are immersed, at least visually, in a universe of shapes and colors and how they relate to one another, a universe from which the language of art issues. This language, as Sigel understands, is no more fixed than the world--our ordinary, unkempt, flea market world--from which it comes. It depends on accident, and it is this that his screenprints, particularly, insist upon. Each print is a "unique multiple," different in color, registration, and sometimes even in the number of repeated images, rather than a series of perfect replications. There is no definitive signification of forms, even in "perfect" replications, much less in reality. In a series of still-life prints, ordinary cardboard boxes of stuff, like baking soda, slide into view from some other place, as though they were always products of the artist's imagination--and indeed they are. They can't be in register because then there would be no place for them to have come from. They wouldn't exist. The still lifes in the show have backgrounds of pink, green, blue, and wine, and as many possibilities as there are colors. Donald Goddard © 2004 |

|

The exhibition ran from March 6 through April 4, 2004, at the Westbeth Gallery, New York, NY 10014. |

Art Reviews Listings - Previous Review - Next Review

Art Review - NYArtWorld.com - NYAW.com. All artwork is copyright of the respective owner or artist. All other material © Copyright 2015 New York Art World ®. All Rights Reserved.

New York Art World ® - Back to Top